“In una città vera si cammina. Sfiori gli altri passanti, sbatti contro la gente… Qui a Los Angeles non c’è contatto fisico con nessuno: stiamo tutti dietro vetro e metallo. Il contatto ci manca talmente che ci schiantiamo contro gli altri solo per sentirne la presenza.”

California, Los Angeles. Non importa, a dire il vero. Che cos’è che definisce ciò che siamo? È l’esperienza a renderci in un certo modo o siamo noi che, essendo in un certo modo, definiamo una certa esperienza? E quando interagiamo con qualcuno, che cosa ai suoi occhi ci identifica in quanto noi? La pelle? La carta di identità? Il libretto degli assegni?

Due detective e la loro frequentazione occasionale. Lei bianca, lui nero. Una famiglia iraniana che campicchia con un 24hours shop. Il procuratore dabbene e la sua consorte. Due ragazzi neri e i furti d’auto notturni. Una coppia naturalizzata americana, il regista remissivo e la moglie sfacciata. Un fabbro ispanico che spera di portare sua figlia in un quartiere migliore. Due poliziotti, lo stronzo e l’idealista.

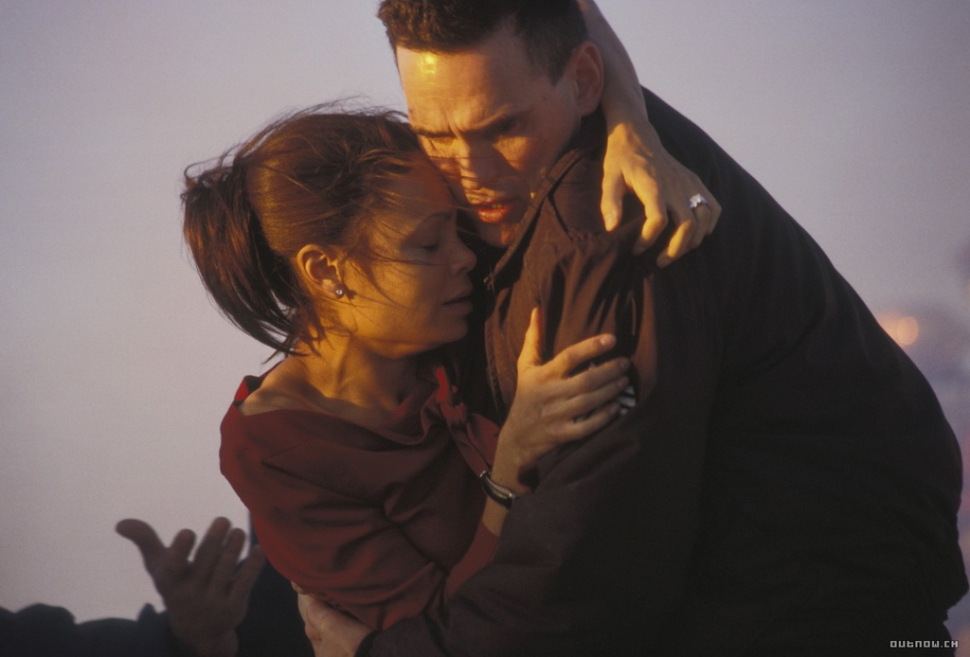

Crash è un film che non sembra conoscere mezze misure. Ci sputa addosso un’America dicotomica, il cui Sogno è solo uno scherzo di cattivo gusto. Un’America post-11 settembre in guerra verso un nemico non identificato, che è potenzialmente chiunque. Uno dopo l’altro, i personaggi sfileranno in una centrifuga alternanza, e faranno esattamente ciò che ci aspetteremmo che facciano. Paul Haggis ci trascina in questo gioco malato, e con una certa sicurezza noi sappiamo da che parte stare.

Ve lo assicuro. Fino al cinquantacinquesimo minuto.

“Tu pensi di sapere chi sei. Tu non hai idea” dice lo stronzo all’idealista. E poi quello stesso stronzo è un figlio affettuoso che aiuta il padre ad andare in bagno. E quello stesso idealista spara a un nero a cui solo poco prima aveva offerto uno passaggio. Il quadro si dipinge con tinte aspre e decise. E di colpo sfuma, mostrando qualcosa di più sottile. Il razzismo si pone come filo conduttore dei vari episodi. Un crescendo di equivoci e di intolleranza in una prospettiva in cui ciò che è un uomo è deterministicamente scritto nella cultura a cui appartiene. Ma questo è niente. Di fondo c’è l’incapacità di stabilire un contatto. Non tra culture. Tra individui. “Ognuno pensa a sé stesso come ad un essere complesso, mentre diviene incredibilmente semplicistico nel giudicare le altre persone” dice Haggis in un’intervista. Perché è difficile decifrare sé stessi, ma lo è ancora di più immaginare un’entità altrettanto indecifrabile. E scontrarsi è l’unica interazione possibile. Crash va oltre il razzismo. Crash è una Babele su larga scala in cui nessuno osa turbare il suono del silenzio.

[divider]ENGLISH VERSION[/divider]

“In any real city, you walk, you know? You brush past people and people bump into you. In L.A., nobody touches you. We’re always behind this metal and glass. I think we miss that touch so much, that we crash into each other, just so we can feel something”. [N.d.T.]

L.A., California. Actually, it doesn’t really matter. What is it that defines what we are? Is it the experience that makes us what we are or we ourselves that define that experience? And when we crash into somebody, what is it that sticks to them as something that makes us really us? Is it our skin? Our ID cards? Our chequebooks?

In a day like any others, lots of lives will be entwined, maybe two detectives with their occasional meeting, a she, white, and a he, black; an Iranian family that carries on with a 24hours shop; the perfect attorney and his wife; two black guys with their stolen cars in the night; a naturalized American couple, a submissive director and a shameless wife; an Hispanic blacksmith who hopes to take away her daughter to live in a better neighborhood; two policemen, the jerk and the idealist.

Crash is a no-half-sizes film. It throws us in a dichotomic America, where The Dream is just a bad taste joke. America, that has demolished all the hierarchies, just ended up creating others. One after the other, all the characters are shown in a centrifugal alternation and they are going to do exactly what we expect them to do, and Paul Haggis brings us in this sick game, almost certain that we know who we think is right.

I can assure you that…. until the fifty-first minute.

“You think you know who you are? You have no idea” that’s what the jerk says to the idealist. And then that jerk is a really good son who helps his father going to the bathroom, while the idealist shoots a black guy only because he offered him a ride home. The whole picture has harsh and powerful colours that slowly fade away to show something thinner. Racism is the thread that links all the episodes. There is a crescendo of misunderstanding and intolerance in a perspective in which a man in something already defined by the culture he belongs to. But that’s nothing, because there is the background inability to create a contact not between different cultures but different individuals. ” Everyone sees himself as a whole being, while is incredibly simplistic when he judges other people”, says Haggis in an interview. It’s really hard trying to decipher ourselves, but it’s harder try to imagine a being just as incomprehensible. That’s when crashing becomes the only possible interaction. Crash goes beyond racism, Crash is our story: a wider Babel, where people would like to overcome their isolation but no one dares to disturb the sound of silence.

Traduzione a cura di Eleonora De Palma