Immaginate Roma con 13 metropolitane.

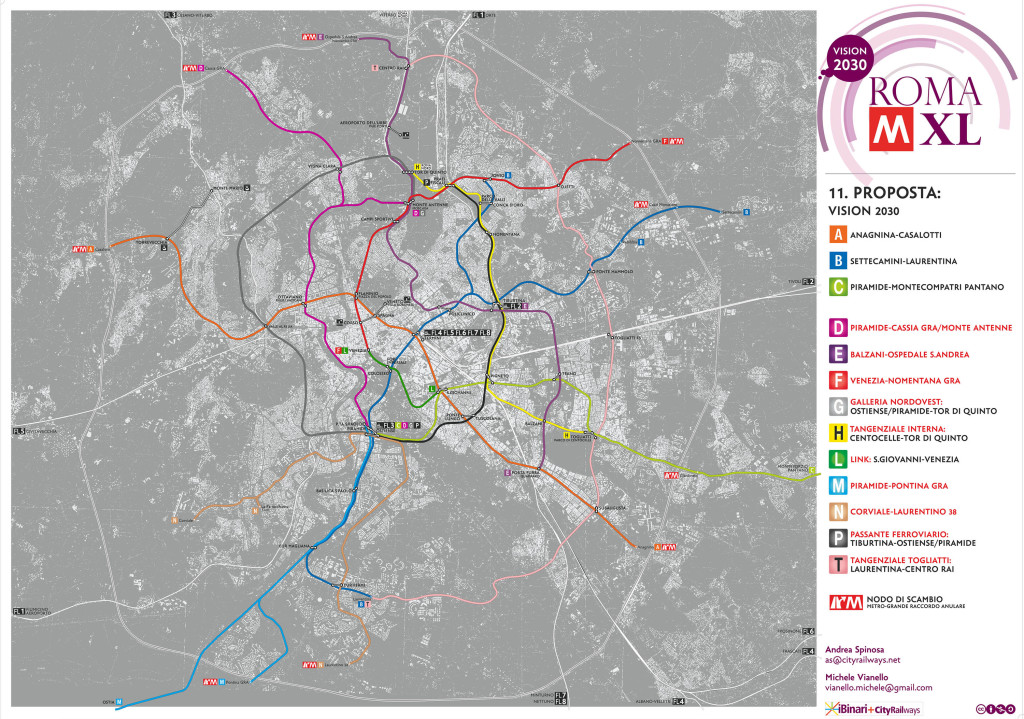

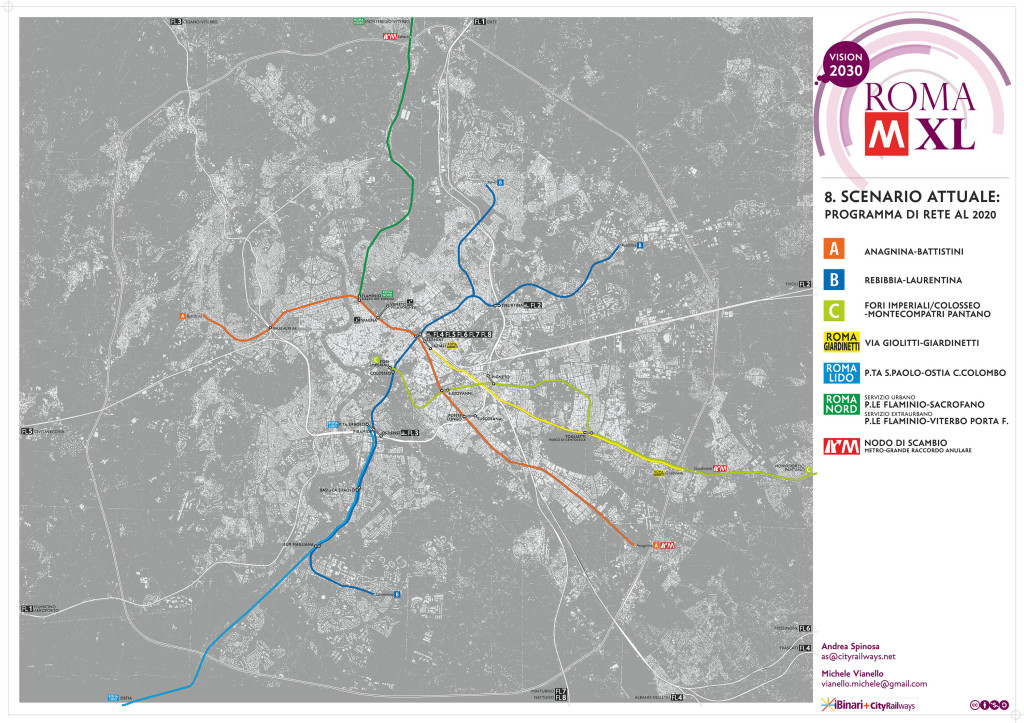

Se pensate sia impossibile date un’occhiata al progetto ROMA MXL di Michele Vianello e Andrea Spinosa. Esperto di smart cities il primo e di metropolitane il secondo, hanno elaborato una proposta per la capitale, forse l’unica in grado di cambiarla davvero.

Abbiamo voluto farci spiegare direttamente dagli ideatori questa idea che potrebbe rivoluzionare il trasporto pubblico romano.

Prima di tutto, com’è nata la vostra proposta Roma MXL? Cosa vi ha spinto a lavorare in modo così approfondito sulla mobilità romana e qual è il vostro obiettivo?

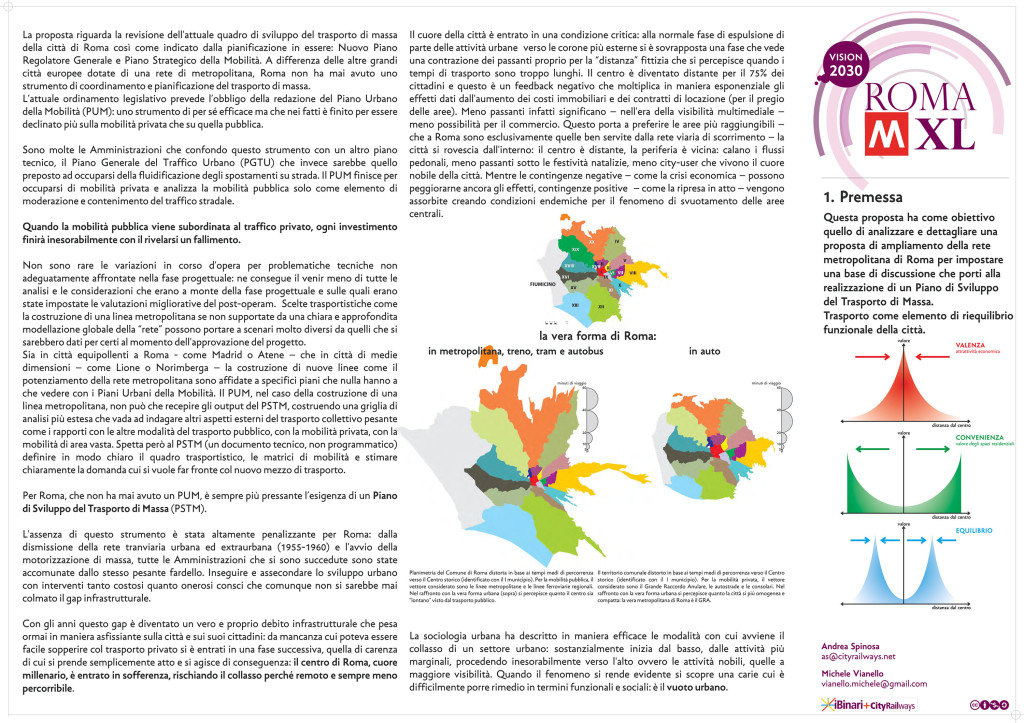

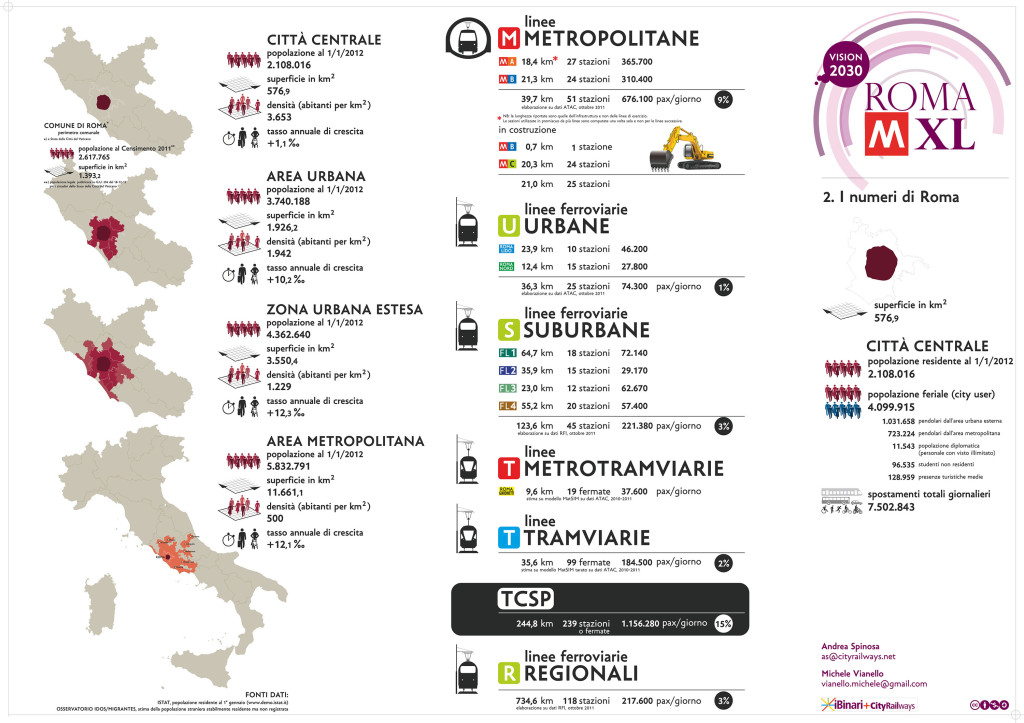

Andrea: Roma MXL nasce dall’incontro di un progettista della Mobilità con un ricercatore in Urbanistica. La piazza in cui ci siamo conosciuti è stata quella virtuale di Cityrailways.it, primo portale italiano del trasporto pubblico su ferro che è diventato una sorta di moderna agorà in cui discutere di buone pratiche. Come responsabile tecnico di Cityrailways, ho sempre cercato di stimolare il dibattito e il confronto sul tema della mobilità, intesa nella sua accezione più ampia. Una visione olistica che ha catturato l’attenzione di Michele, che in quel momento si stava occupando di dispersione urbana. Assenza di governance della mobilità e un’urbanizzazione dispersa e frammentaria sono i due aspetti della moderna “Questione urbana” italiana. E Roma ne è l’archetipo.

Michele: Andrea aveva pubblicato un piccolo studio sulla metropolitana di Roma con molte idee interessanti. L’ho contattato perché volevo includere in una nuova riflessione congiunta dei temi che ritenevo importanti. Negli ultimi 20 anni gli urbanisti italiani sembrano aver scoperto la dispersione urbana, che è fenomeno decisamente più antico, e se ne occupano in maniera compulsiva. Sia in positivo, più o meno allegramente accettando lo spontaneismo della dispersione della Brianza, del Veneto orientale, e ormai di tutta Italia, come un fenomeno connaturato alle nostre strutture sociali e sistemi produttivi; sia in negativo, additando il consumo di suolo e la dispersione come la causa di tutti i mali. Pur orientandosi più verso la seconda ipotesi questo studio, anche per questioni anagrafiche degli autori, ha optato per un approccio molto pragmatico: capire come la mobilità possa dare nuovo senso al rapporto tra città consolidata e territorio della dispersione. Roma, per le sue caratteristiche, era un caso perfetto.

Nel vostro lavoro criticate come sono state portate avanti le cose finora a Roma. Una visione del futuro limitata e incerta, eccessivi passi indietro, ripensamenti e soprattutto la scarsa capacità di creare un effetto rete. Tralasciando per un attimo le infrastrutture, quanto è indietro la mentalità di Roma riguardo al trasporto pubblico rispetto alle altre capitali europee?

A: A Roma non esiste alcuna visione del futuro: l’urbanistica è scomparsa dagli anni Ottanta del secolo scorso ed ogni atto progettuale pubblico è declinato esclusivamente in chiave edilizia. Ogni azione si svolge astraendo dal contesto e dal tempo: non esiste né una visione orizzontale – come si relaziona l’intervento con le parti di città al contorno – né una visione verticale – cioè cosa accadrà domani, rammentando quanto verificatosi ieri. Gli ultimi PEEP, Piani di Edilizia Economica e Popolare, sono stati gli ultimi scampoli di una progettualità che si sforzava di far funzionare una città cresciuta (esplosa) in maniera spontanea nell’arco di un trentennio, a partire dagli anni Cinquanta. La politica della gestione commissariale ha trasformato tutto in un emergenza: il traffico; i rifiuti e persino le piene autunnali del Tevere. Tutti elementi che sono ordinari nella altre metropoli, a Roma diventano straordinari. E siccome lo straordinario non è prevedibile, la pianificazione è inutile e anche la progettualità pubblica diventa immediata, spontanea, come lo erano le nuove palazzine nel boom edilizio degli anni Settanta.

Per questo non si può parlare di arretratezza ma di una visione amministrativa non solo limitata, ma distorta e strutturata per contrastare ogni forma di “correzione”. A Roma è difficile cambiare perché c’è la convinzione diffusa che non ci sia alternativa. In realtà non esiste e non è mai esistito alcun “modello Roma”, né in senso positivo né in senso negativo. Solamente un castello di convinzioni che si giustificano a vicenda.

Un esempio per il tutto: a Roma il traffico è ingovernabile e questo giustifica provvedimenti straordinari. Si sceglie di incentivare con soldi pubblici non la mobilità lenta, come la ciclabilità, ma l’acquisto dei motocicli. Quando il parco dei veicoli a due ruote diventa il più grande d’Europa ci si rende conto che una delle cause dell’incontrollabilità del traffico è proprio nella quota di questi veicoli (24% in ora di punta, contro una media tra le grandi città europee inferiore al 7%). A Roma se acquisto un motorino non lo faccio per utilizzarlo come un auto, mantenendo distanze di sicurezza e facendo attenzione alle precedenze ma per “svicolare”. Nessuno è mai stato multato per aver “svicolato” con il motorino. Eppure nel resto d’Europa chi viaggia in motorino viaggia entro il flusso del traffico, superando in sinistra solo se c’è abbastanza spazio. Lo svicolare è un’eccezione e non la norma.

Si sceglie di evitare ogni provvedimento di moderazione della velocità delle auto (come i cordoli rialzati per proteggere le corsie dei mezzi pubblici) pur di non dare l’impressione di voler contrastare la libertà di utilizzare l’auto. È così che si è fatto di Roma la città europea con più pedoni investiti sulle strisce; più incidenti stradali per abitante e più incidenti mortali per le due ruote. E la città in cui le spese sociali della mobilità sono le più alte in assoluto.

M: Più che essere indietro a Roma una “mentalità”, come dici, del trasporto pubblico deve essere ricostruita da zero. Questo è senz’altro tragico, ma da un certo punto di vista, mantenendo una prospettiva ottimista, apre delle opportunità enormi. Queste si possono cogliere imparando dagli errori, anche quelli che Andrea cita, e guardando alle esperienze positive: il tram 8, la ristrutturazione della ferrovia (ex) FR3 tra Trastevere e Ipogeo degli Ottavi, o anche i filobus sulla direttrice Termini – Montesacro. Quella spinta propulsiva è pero esaurita da tempo. I vantaggi che si possono vedere nella situazione attuale sono piuttosto nella libertà di porsi obiettivi nuovi. Fare un paragone con le infrastrutture delle capitali europee intese come le “classiche” metropolitane di Londra e Parigi tra la fine del ‘900 e la Seconda Guerra è però un errore. Si trattava di grandi capitali borghesi (in senso storico) di imperi coloniali mondiali, stiamo parlando di una fflusso di capitali, merci, persone che ha segnato la storia urbana mondiale. Dividendo in quattro quadranti Londra, con l’incrocio degli assi nella City, la Underground si è per moltissimo tempo sviluppata per la grande maggioranza della sua estensione nel quadrante di Nord Ovest, il cosiddetto West End. Parigi ha un separazione storica tra città intra muros e banlieue di cui il Métro è uno specchio fedele. Quell’epoca è finita (e aggiungerei che è un bene), e Roma credo non avrà mai un metropolitana come quelle (e aggiungerei che potrebbe essere un bene). Se oggi ci sforziamo di immaginare modelli di trasporti che hanno l’ambizione di essere validi per i prossimi 100 anni abbiamo l’occasione e il dovere di farlo in modo inclusivo. Le stesse Londra e Parigi hanno completamente rinnovato le loro strategie.

Lamentate la mancanza a Roma del PSTM (piano strategico del trasporto di massa). Cos’è questo strumento e come vorreste svilupparlo?

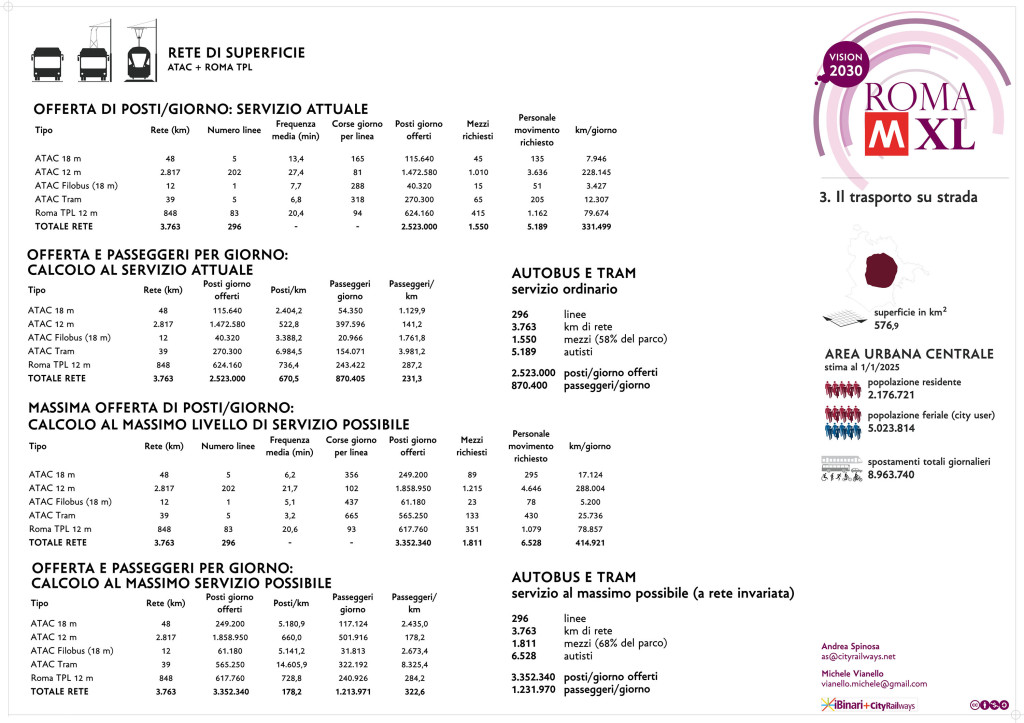

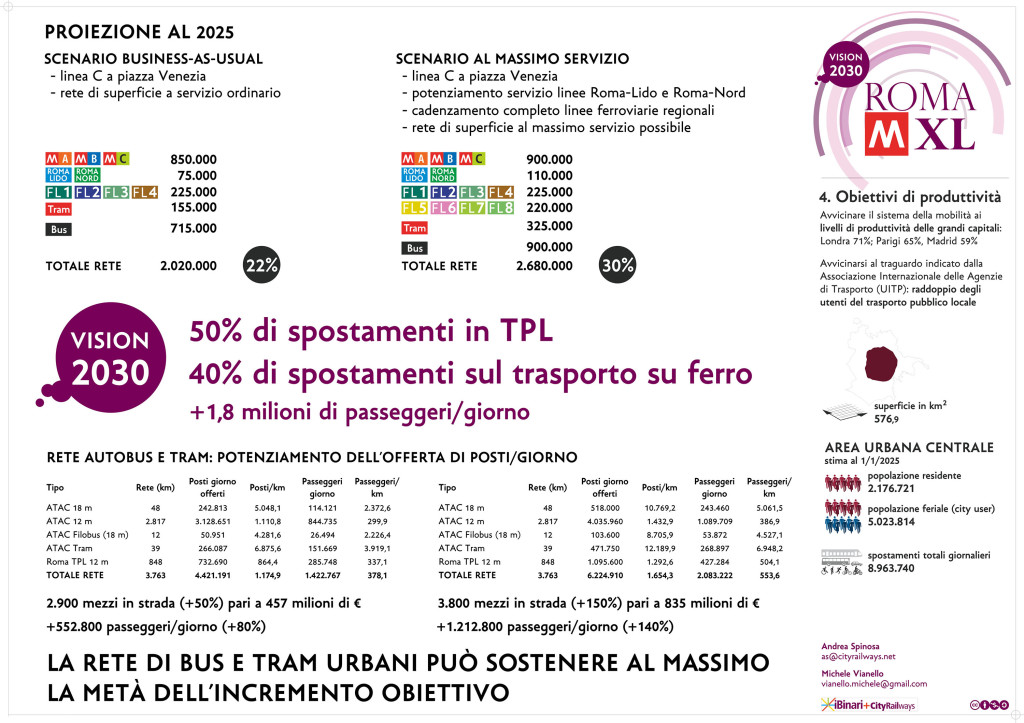

A: È il Transport Plan nordamericano, oppure il Plan des Désplacements Urbaine francese. Si tratta del Piano Regolatore del Trasporto di Massa ed è tutt’altra cosa da come sono stati declinati in Italia questi strumenti. Basti pensare che qui il legislatore ha pensato bene di individuare due strumenti uno per la mobilità privata (il PGTU, obbligatorio) ed uno per la mobilità pubblica (il PUM, volontario). La subordinazione della mobilità pubblica a quella privata è rafforzata dal fatto di non distinguere in alcun modo la mobilità metropolitana (di massa) dal comune trasporto su gomma (la rete dei bus). Pianificare e progettare mezzi di trasporto da 300 o 1.000 passeggeri alla volta non è la stessa cosa di muovere al più 80 persone in un bus su strada. Pianificare il trasporto urbano significa far ripartire le città che sono il motore economico del Paese. Iniziare dai grandi nodi metropolitani, come Roma, significare lanciare il Paese verso il futuro, oltre le contingenze della crisi.

M: Credo che ormai si chiami Piano Strategico Mobilità Sostenibile, e come in molti altri casi le etichette “sostenibile” (o “smart”, etc. ) seguono programmi di finanziamento e ricerca europei senza tanto riflettere su cosa significhino, che è spesso un peccato. Si tratta di uno strumento di “indirizzo”, parola passepartout di tutti gli strumenti urbanistici che non hanno necessariamente stringenza attuativa. Può essere molto utile, e lo è stato in molte occasioni, dove le pratiche di buona amministrazione lo hanno reso un’occasione per pensare il futuro. Ancora una volta, è interessante che esista uno strumento come questo, come usarlo però è una questione di scelte e obiettivi. Se si tratta di gestire l’ordinario in maniera mediocre stiamo dando un nome pomposo a qualcosa che si è sempre fatto, se tratta di disegnare molte linee in centro perché ci sono anche a Parigi stiamo peccando di un’ingenuità intollerabile. Pur non avendo redatto un piano di quel tipo abbiamo cercato, seguendo la regole delle 4s, di indicare la strada verso di una piccola utopia ma, se mi passi la contraddizione, razionale e realistica.

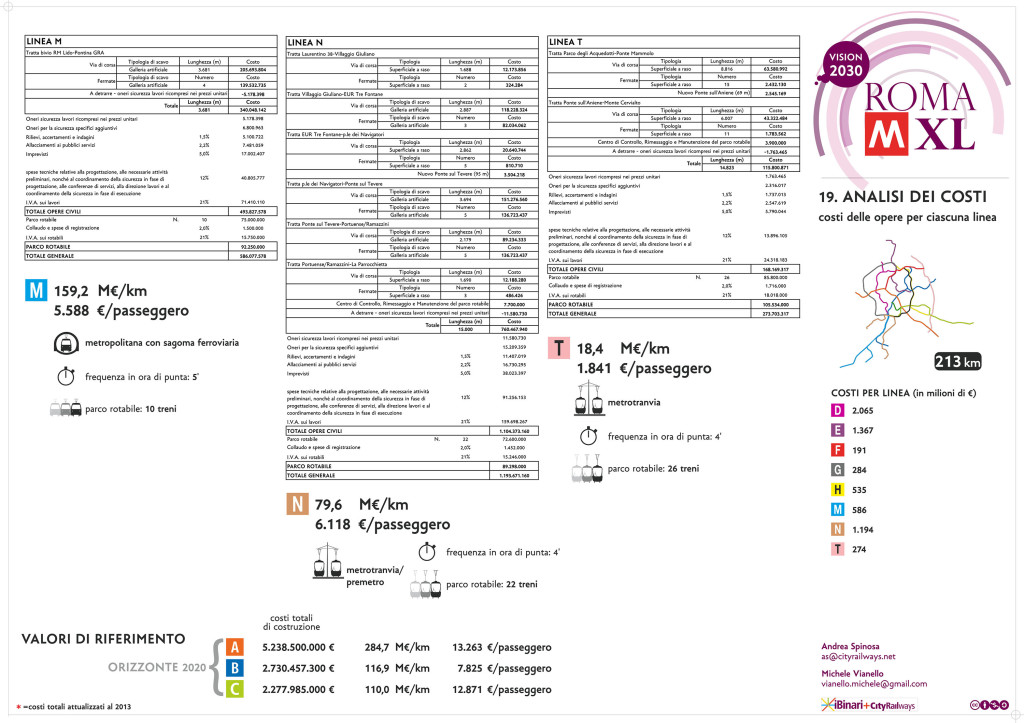

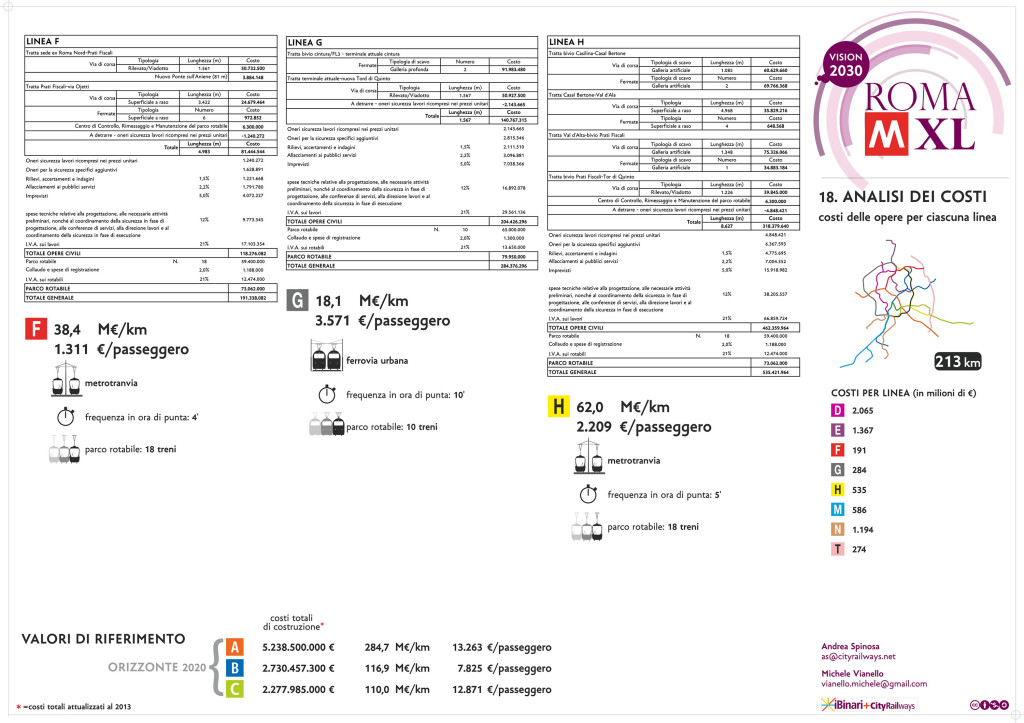

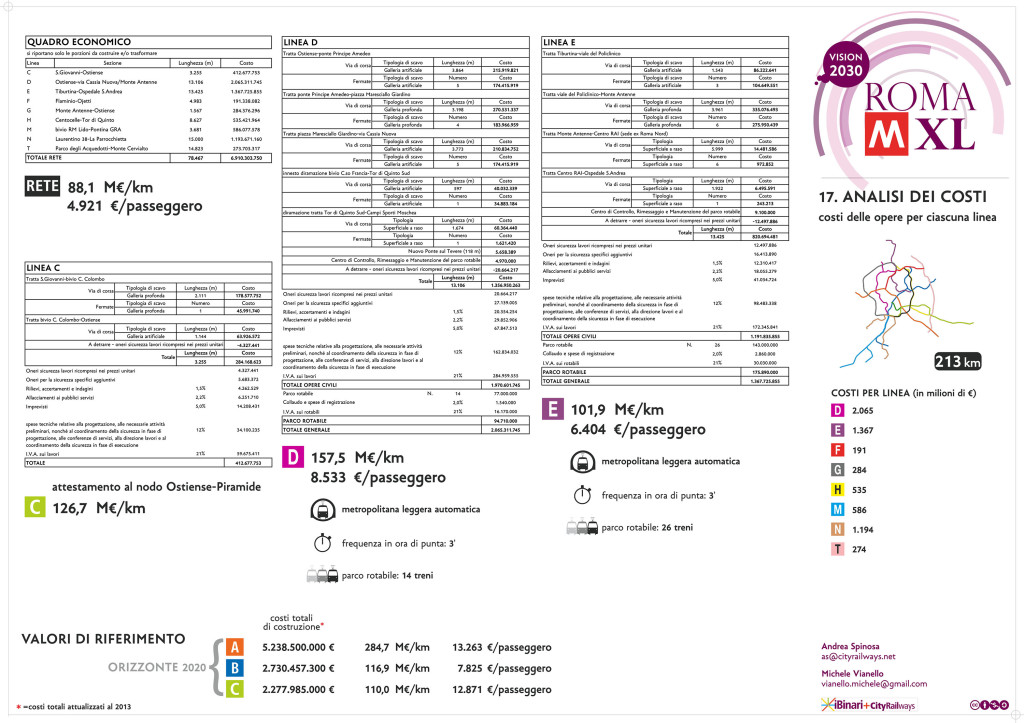

Nel vostro progetto parlate di un investimento di quasi 7 miliardi di euro. In tempi di crisi come questi, una proposta del genere potrebbe essere vista come un azzardo, una pazzia.

Pensate sia uno sforzo economico fattibile da parte degli enti preposti (Stato, Regione, Comune, ecc.) e credete sia necessario coinvolgere nell’opera anche i privati, magari attraverso il project financing?

A: Quando si parla di numeri nulla è giudicabile in senso assoluto. Sappiamo che incrementare di 2 punti percentuale (200.000 passeggeri) la quota di persone che giornalmente a Roma si spostano con il mezzo pubblico equivale a creare ogni anno un controvalore di un punto percentuale di PIL. A Roma il PIL annuo è prossimo ai 74 miliardi di €: parliamo quindi di un incremento di 740 milioni di €. Movimentare 200.000 persone significa creare ad esempio una metropolitana ad alta capacità per un investimento complessivo di almeno 5 miliardi. Il tempo di ammortamento dell’investimento è di 6,7 anni. Il tasso di interesse equivalente è pari al 100% diviso il tempo di ammortamento ovvero il 15%. Investire con un tasso di interesse pari al 15%/anno non vi sembra vantaggioso?

La tecnologia di trasporto che garantisce la più alta efficienza, in ambiente urbano, è il trasporto elettrico alimentato da filo: una tecnologia ormai consolidata,con bassi costi di esercizio e manutenzione. Se i carichi lo consentono la fisica ci dice che, riducendo il coefficiente d’attrito e quindi passando dal contatto gomma/strada a quello ferro/ferro abbiamo un ulteriore vantaggio. Questo non significa che sarà sempre così ma abbiamo la certezza che per i prossimi 30 anni filobus, tram, ferrovie urbane e metropolitane continueranno ad essere le tecnologie a maggiore redditività.

Perché il trasporto pubblico elettrico è vantaggioso? Perché riduce al minimo l’inquinamento dell’aria proprio dove la concentrazione di persone è maggiore; perché permette di spostarsi a costi 100 volte inferiori a quelli che si dovrebbero sostenere utilizzando la propria macchina; perché permette agli Amministratori e agli Investitori di conoscere a priori quali saranno le aree della città in cui si concentreranno i maggiori flussi di persone e quindi permette di capitalizzare questi flussi favorendo gli investimenti privati.

Ma la maggior parte di questo guadagno è un guadagno sociale: una minore incidenza di patologie correlate alle cattive condizioni ambientali significa una minore spesa sanitaria; cittadini più sani e trasporti più veloci significano più ore di lavoro ma anche più tempo libero; meno soldi spesi in trasporto significa avere più soldi da spendere. Il trasporto pubblico muove persone ma anche idee: non è un caso che le città in cui si vive meglio nel mondo siano a seconda delle classifiche Melbourne, Toronto, Sydney, Vancouver, Stoccolma, San Francisco: tutte città in cui il rapporto tra mobilità pubblica e privata è esattamente il contrario di quello di Roma.

Se il guadagno è sociale è giocoforza che i privati possano al più compartecipare all’investimento per nuove infrastrutture. Se il guadagno è per i cittadini è lo Stato, che è chiamato a gestire la ricchezza collettiva, che deve investire al 15%/anno. È non un discorso di stampo socialista: basti pensare che in Cina è lo Stato che sta investendo nella realizzazione di 7mila km di metropolitane e 20mila km di nuove tramvie. Ma anche in USA è lo Stato che, tramite un fondo apposito – il “Tiger” – finanzia in maniera esclusiva tranvie e metropolitane.

M: Il progetto mette l’accento su 4 diversi tipi di sostenibilità, inclusa quella economica. In una situazione in cui le spese sanitarie fossero controllate ed efficienti la sostenibilità sarebbe possibile. Sappiamo però che queste condizioni non sono quelle correnti, e che questi 7 miliardi sarebbero da anticipare su risparmi futuri che sono solo ipotetici. Basta visitare un ospedale del Lazio, ad esempio di Formia, per capire di cosa sto parlando: diversi milioni servirebbero solo per ristrutturare l’edificio, chissà quanti per renderlo veramente adeguato. Questi calcoli hanno però ugualmente un valore: quello di riflettere sul valore e il senso degli investimenti pubblici sui trasporti. Il costo delle gallerie TAV sotto Bologna e Firenze raggiungerà costi spropositati, mentre la riprogettazione dei nodi avrebbe probabilmente liberato fondi ingenti da utilizzare in quelle città in modo più adeguato. Inoltre lungo il presente tracciato e a questi ritmi di costruzione la linea C potrebbe finire per costare una cifra non troppo inferiore ai 7 miliardi di euro.

Per quel che riguarda il project financing, le esperienze italiane del passato ci hanno dimostrato che si tratta di una finzione letteraria. Forse la M5 di Milano mi smentirà, ma finché nel partenariato pubblico privato in salsa italiana il rischio di impresa sarà garantito da fondi pubblici il project financing potrà più appropriatamente essere chiamato investimento privato tutelato dai contribuenti a rischio zero. Potrebbe anche essere uno strumento utile, ma solo se si ha la certezza che le infrastrutture siano disegnate nell’interesse della collettività e non di chi le costruisce, e questo comporta diversi cambiamenti, ad esempio nel funzionamento degli appalti, ma anche nella procedura e nella cultura del disegno delle infrastrutture. Nel frattempo suggerisco di leggere piuttosto un romanzo. Il project financing è uno strumento messo in discussione in diversi contesti, e quello italiano al momento e a mio avviso non consente un suo utilizzo proficuo.

[irp posts=”792″ name=”Roma MXL, una chance per la Capitale – Seconda Parte”]

[divider]ENGLISH VERSION[/divider]

First of all, how did your Rome MXL’s proposal arise? What pushed you to work in such in-depth way on roman mobility and what is your purpose?

Andrea: Rome MXL buds from the encounter between a Mobility designer and a researcher in Urbanism. We met in a virtual square, Cityrailways.it, the first Italian portal on public railroad transport, which has become a kind of modern agora, in which you can talk about good practices. As technical manager of Cityrailways.it, I have always tried to encourage debates and comparisons about mobility, in his broader sense. A holistic view that caught Michele’s attention, who was dealing with urban dispersion, at that time. The absence of mobility’s governance and a scattered and piecemeal urbanization; these are the aspects of the Italian “Urban Matter”. And Rome is its epitome.

Michele: Andrea published a small and interesting research about Rome’s subway. I got through to him because I wanted to insert a new reflection with some themes I considered important. In the last 20 years, Italian city planners seem to have discovered urban dispersion, even if it is a quite aged phenomenon, and they are compulsively interested in it. Both positively, accepting, more or less happily, as a phenomenon inborn to our social and productive system, the spontaneity of Brianza’s dispersion or of oriental Veneto’s and by then of the entire Italy’s; and negatively, pointing to the ground consumption and dispersion as the cause of all the evil. Even if this survey is more oriented toward that second option, because the age of the authors too, we opted for a more pragmatically approach: to understand how mobility could give a new meaning to the relation between the stabilized city and the dispersion territory. Because of its characteristics, Rome was the perfect example.

In your work, you criticize how things have been carried out so far in Rome. A limited and uncertain vision of the future, too many back steps, thoughts and especially the lack of ability to create a network effect. Leaving aside for a moment infrastructures, how far is Rome’s mentality about public transport compared to other European capitals?

A: There is no vision of the future in Rome. City planning has disappeared since the 80s of the last century, and every act of design is declined only in construction building. Each action takes place in abstraction from context and time: there is neither a horizontal view – how it relates to the intervention with the parts of the city boundary – either a vertical vision – that is what will happen tomorrow, remembering events that took place in the past. The last plans for economic and popular buildings were the last remnants of a project that was trying to run a city grew up (exploded) spontaneously in a period of thirty years, starting in the 50s. The policy of the management commissioner has turned everything into an emergency: traffic, garbage and even the autumn floods of the Tiber. All the elements that are commonplace in other cities become extraordinary in Rome. And because the extraordinary is not predictable, planning is useless and even public planning becomes immediate, spontaneous, as the new buildings in the 70s’ boom were.

For this reason you cannot speak of underdevelopment but of an administrative vision, which is not only limited, but also distorted and structured to oppose any form of “correction”. In Rome, it is difficult to change because there is a widespread belief that there is no alternative. In fact, does not exist and has never existed any “Rome model”, nor in a positive or in a negative way. There is only a castle of beliefs that justify each other.

One example for all: Rome traffic is ungovernable, and this justifies extraordinary measures. They prefer to subsidize with public money not the slow mobility, like cycling, but the purchase of motorcycles. When the two- wheelers park is the largest in Europe, you realize that one of the causes of uncontrollability of traffic is exactly in the percentage of these vehicles (24% during the rush hour, compared with an average less than 7% between major European cities). In Rome, if you buy a scooter you do not use it were a car, keeping a safe distance and paying attention to priorities, but to “slip away”. Nobody has ever been fined for “wriggling” with the scooter. Yet, in the rest of Europe, those who travel on a motorbike within the flow of traffic, pass on the left only if there is enough space. Wriggling is an exception, it is not the norm.

You choose to avoid any measure of moderation in speed (such as curbs to protect the public transport lanes) in order not to give the impression of wanting to counteract the freedom to use the car. That is why Rome is the European city with more pedestrians hit on the strips; more accidents per inhabitants and more fatalities caused by two wheel vehicles. Rome is the city in which the social costs of mobility are the highest ever.

M: Rather than being far, in Rome, a “mentality”, as you said, for public transport needs to be rebuilt from zero. This is certainly tragic, but from a certain point of view, maintaining an optimistic outlook, it opens enormous opportunities, learning from mistakes, even those that Andrea mentioned, and looking at the positive experiences. Such as the tram number 8, the restructuring of the railway (former) FR3 between Trastevere and Ipogeo degli Ottavi, or the trolley buses on the line Termini – Montesacro. However, that propelling force is already out of stock. The benefits that can be seen in the current situation, are rather in the freedom to set new goals. It is a mistake to make a comparison with the infrastructure of the European capitals, meant as the “classic” London and Paris’ underground built between the end of ‘900 and the WWII. They were great bourgeois capitals (in the historical sense) of worldwide colonial empires. We are talking about a flow of capitals, goods, people who made the universal urban history. Dividing London into four quadrants, with the intersection of the axes in the City, the Underground was developed, for a very long time, for the vast majority of its extension in the North West quadrant, in the so-called West End. Paris has a historical separation between the town intra muros and the banlieue of which the Métro is a faithful mirror. That era is over (and I would add that it is good), and I think Rome will never have a metro like those (and one more time I would add that it might be a good thing). If today we strive to imagine models of transport that have the ambition to be valid for the next 100 years, we have the opportunity and the duty to do it in an inclusive manner. London and Paris as well have completely renovated their strategies.

You complain about the lack of a strategic plan for mass transport in Rome. What is this about and how would you develop it?

A: It is the American Transport Plan, or the French Plan des Désplacements Urbaine. It is the Master Plan for Mass Transportation and it is quite far from how they were declined in Italy. Just think that here legislature has identified two instruments, one for private mobility, which is mandatory, and one for the public mobility, which is voluntary. The subordination of the public to the private mobility is enhanced by the fact that there is not distinction between the metropolitan mobility (mass) and the ordinary road transport (the bus network). Plan and design transportation for 300 or 1,000 passengers at a time, is not the same thing as moving as 80 people in a bus on the road. Planning the urban transport means to restart the cities, which are the economic engine of the country. Starting with large metropolitan nodes, such as Rome, means throw the country into the future, beyond the contingencies of the crisis.

M: I think today it’s called Strategic Plan for Sustainable Mobility, and as in many other cases, the label “sustainable” (or ” smart “, etc.) follows European research funding programs, without reflecting so much on what it means. And often this is a pity. It is a tool whose aim is to “address”, the key word of all the planning instruments that don’t have necessarily a stringency implementation. It can be very useful, and has been useful in many occasions, like when the practices of good governance have made it an opportunity to think about the future. Again, it is interesting that there is a tool like this, how to use it, however, is a matter of choices and goals. If the aim is to manage the ordinary in a mediocre way, we are giving a pompous name to something that it always been done. If the aim is drawing a lot of lines in the center, because in Paris there are a lot too, we are also sinning of an intolerable ingenuity. Despite not having drawn up a plan of that kind, we tried, following the rules of the 4s, to point the way toward a small utopia, but, if I can throw a contradiction, it is also rational and realistic.

In your project, you speak of an investment of nearly € 7 billion. In times of crisis such as these, a proposal like this could be seen as a gamble, madness. Do you think it is a feasible economic effort on the part of authorities (State, Region, District, etc…) and, do you believe it is necessary to involve the private in the work too, perhaps through a project financing ?

A: When talking about numbers, nothing can be judged in an absolute sense. We know that increasing by 2 percentage points (200,000 passengers) the proportion of people daily travelling in Rome by public transport, it is the same as creating every year a similar of one percentage point of GDP. In Rome, the annual GDP is close to 74 billion €. We are therefore speaking of an increase of 740 million €. Moving 200,000 people means creating, for example, a high-capacity underground for a total investment of at least 5 billion $. The amortization period of the investment is 6 or 7 years. The interest rate is equivalent to 100% divided by the amortization period, which is the 15%. Don’t you find it convenient?

The transport technology that guarantees the highest efficiency in the urban environment, is the electric transport powered by thread: a funded technology, with low running costs and maintenance. If loads hold out, physics states that, by reducing the coefficient of friction, and then passing from contact rubber/road to the iron/iron, we have an added advantage. This does not mean that it will always be like this, but we are certain that for the next 30 years trolley buses, trams, urban and underground railways will continue to be the more profitable technology.

Why does the electric public transport is convenient? Because it minimizes pollution right where the concentration of people is greater, allowing you to move to costs 100 times less than those using your car. It allows Administrators and Investors to know a priori what the areas of the city in which there will be the major flows of people, and then it allows you to capitalize on these flows by encouraging private investments.

However, most of this profit is a social earnings. A lower incidence of diseases related to bad environmental conditions, means lower health care costs. Healthier citizens and fastest transport mean more hours of work, but also more spare time. Less money spent on transport means you have more money to spend. Public transport moves people but also ideas. It is no coincidence that, depending on the charts, the best liveable cities in the world are Melbourne, Toronto, Sydney, Vancouver, Stockholm, San Francisco. Those are cities in which, the relationship between public and private mobility is exactly the opposite of that of Rome.

If the profit is social, it is clear that privates may share in the profits to invest for new infrastructures. If the profit is for the citizens, the State has to manage the collective wealth, which must invest 15% year. This is not a socialist discourse. Actually in China the State invests in the construction of 7 thousand km of undergrounds and 20 thousand km of new tram systems. But even in the U.S. is the State that, through a special funds – the “Tiger” – finances tramways and subways exclusively.

M: The project focuses on 4 different types of sustainability, including the economic one. In a situation where health care costs were controlled and efficient, sustainability would be possible. But we know that these conditions are not the current ones, and that these 7 billion € would be anticipated on future savings, that now are only hypothetical.

Just visit a hospital in Lazio, Formia’s for example, to understand what I’m talking about: several million would be necessary only to renovate the building. Who knows how much to make it really appropriate? These calculations have, however, also a value: to reflect on the value and meaning of public investments on transport. The cost of the TAV tunnels under Bologna and Florence will achieve disproportionate costs, while the redesign of the hubs would probably release substantial funds to be used in that city in a more appropriate way. Furthermore, along this path and these rhythms of construction, the C line could cost a figure not too much less than 7 billion €.

Concerning the project financing, the Italian experience of the past have shown us that it is just fiction. Perhaps the Milan’s M5 line could deny me, but as long as in the public-private partnership in Italian dressing the business risk will be guaranteed by public funds, the project financing may be more appropriately called private investment, protected by the taxpayers with no risk. It could also be a useful tool, but only if you are sure that the infrastructures are designed in the public interest, and not in the person who builds them. This involves several changes, such as in the operation of the contracts, but also in the procedure and in the culture of the design of the infrastructures. In the meantime, I suggest you to read a novel. Project financing is a tool brought into question in different contexts, and the Italian one, at the time and in my opinion, does not allow its profitable use.

Traduzione a cura di Daniela De Angelis